Howard’s Haviland

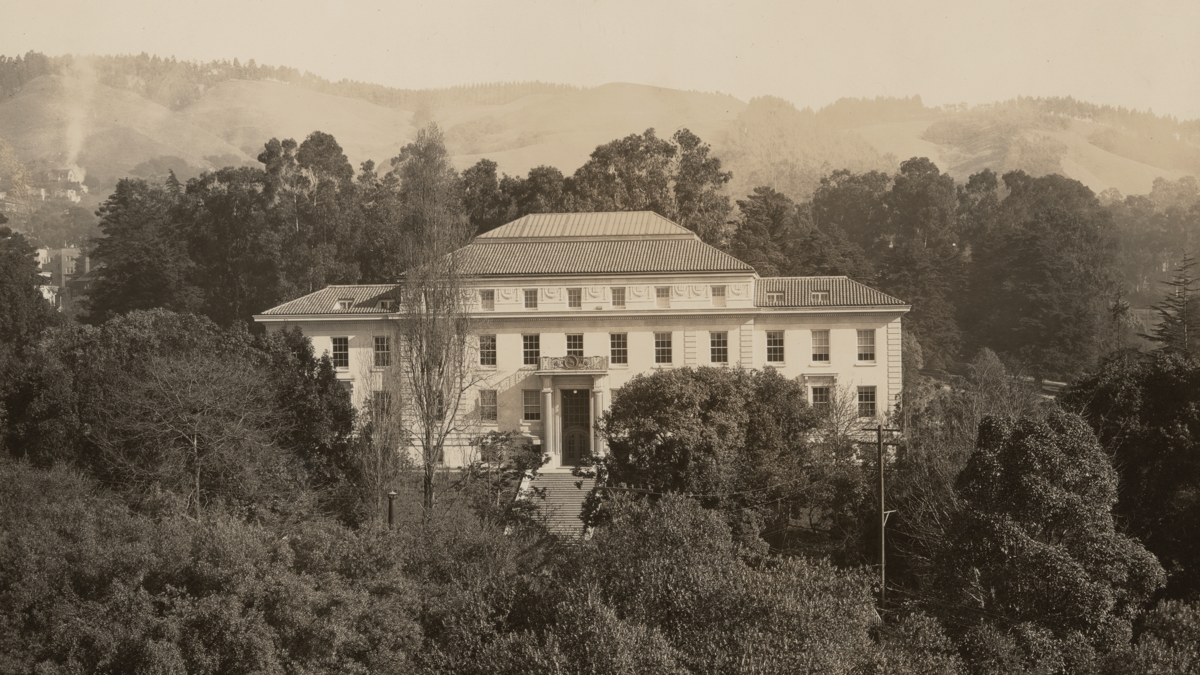

Haviland Hall was completed in 1924, one of a collection of buildings by campus architect John Galen Howard (1864-1931) that transformed the Berkeley campus.

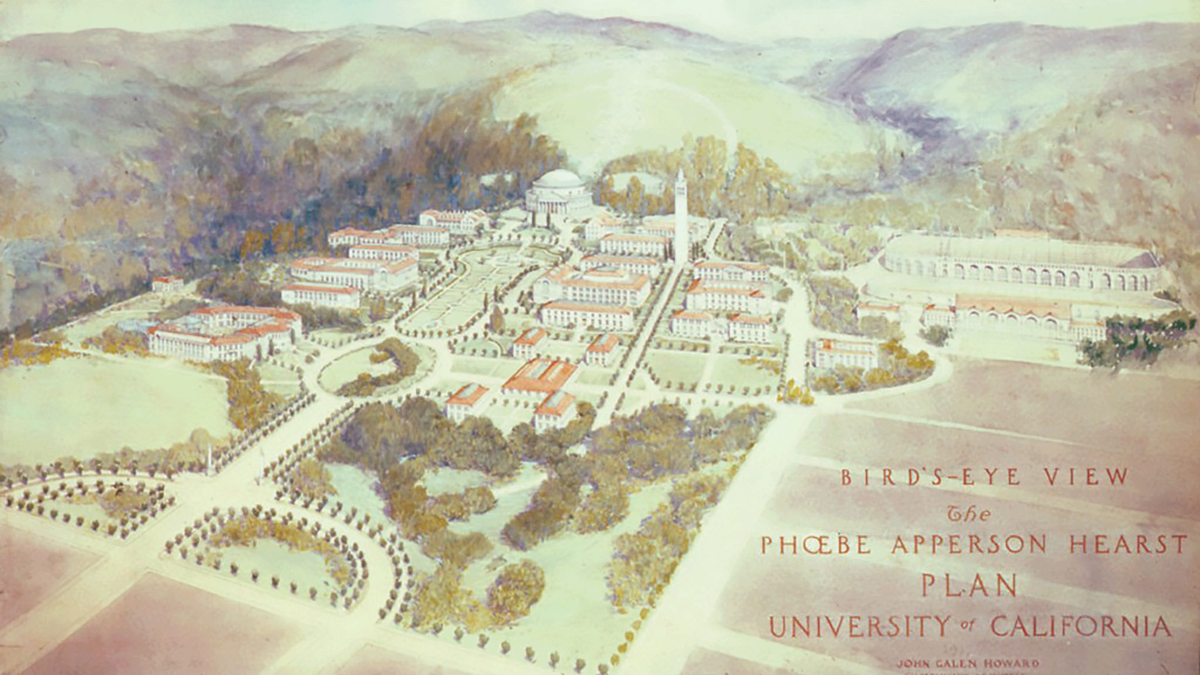

Inspired by California’s growing importance, and with the backing of Phoebe Apperson Hearst, a major benefactor of the early university, the university launched an international competition in 1898-99 for master plans for the development of the campus. French architect Émile Bénard won the competition—Howard placed fourth—but differences with Benard resulted in his departure in 1900, and Howard was appointed as supervising architect in 1901.

Howard’s designs reflect his training at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Although originally appointed to implement Benard’s plan, Howard reshaped it into his own, developing a “City of Learning” that oriented the central axis of the campus toward the Golden Gate. The campus landmarks built during his tenure include the Hearst Memorial Mining Building (1902-7), the Hearst Greek Theatre (1903), California Hall (1905), Doe Library (1911-17), Sather Gate (1910), Durant Hall (1912), Wellman (formerly Agriculture) Hall (1912), the Campanile (1914), Wheeler Hall (1917), Gilman Hall (1917), and Hilgard Hall (1918).

Plans for a new home for the School of Education were already in progress in 1920 when the university received Hannah Haviland’s bequest. John Galen Howard was assigned to design the new building, one of his last, following the Phoebe Apperson Hearst model of a red-tiled roof and a granite or concrete exterior. Throughout 1921, no site had been selected, though the site of the old North Hall was being discussed. By then, the superstructure of that building had been demolished and only the ground floor remained, adjacent to Doe Library and housing the student cooperative store.

But while the final site had not been determined, the design of the new building was firmly settled in Howard’s mind. This is evident from the earliest sketch of the new building Howard made in February 1921. While captioned as a “Sketch for a new North Hall,” the building is virtually identical to the design of Haviland Hall as it would be completed.

By January 1922, a new location was selected across the Botanical Garden from Doe Library for a symmetrical balance along a north and south line with California hall, as the campus still intended to rebuild both North and South halls of granite, keeping with the designs of Doe Library and Wheeler Hall. Haviland Hall, by contrast, was to be built entirely of concrete, but with its “red tiled roof and deep alcoves [it] will cause one to think at first glance that they are looking at California hall,” according to the Daily Californian.

The new building was to be 176 feet long by 72 feet wide, of five stories, including a basement and sub-basement, and featuring furniture of oak and interior trim of Oregon pine. There would be 52 lecture and seminar rooms, as well as a library, which, it was hoped, would relieve congestion at the main library. The new building would have a kitchen, an exhibition room, and several laboratory rooms. Outside, “facing a little to the south of west the hall will look out over the bay and long wide brick steps furnish an admirable lounging place for students,” while each floor was to have an auditorium with a platform and movie equipment. The third floor auditorium would be in the “exact center of the structure. This is the largest of all and will be lighted by 60, 150-watt lights hung so as to give perfect diffusion.” “Altogether,” declared the newspaper, “the building will be the most completely equipped on campus.”

This was to be a building to last. “University buildings were constructed to remain for over a thousand years,” the Daily Cal proclaimed in its September 17, 1923, issue. “Come back to the University campus in the year 2023 and you will no doubt observe Wheeler hall, the Library, the Chemistry building, and Boalt hall standing intact, with their white granite as strong and secure as they are today. For the newest buildings on the campus were constructed to last over a thousand years.” According to John Galen Howard, these buildings were made “so that every room is most useful” and built in as permanent a manner as buildings can be built, with steel construction and a design which adds strength, making them “practically everlasting.”

“With every part of the structures constructed as strongly as possible,” Howard declared, “the University authorities need not worry about replacing them for generations to come.”

When it was finally completed in 1924, it was hailed as a magnificent and significant addition to the campus. “Art critics have diagnosed this latest addition to the University,” said the Daily Californian, “and have expressed their belief that Haviland hall will take its place on par with the Library building, Wheeler hall, and other campus buildings, which have attracted wide-spread notice because of their architectural beauty.” The May 1924 issue of the Western Journal of Education carried a cover story on the new hall, declaring that “The building, as fine a one as man can build of steel and artificial stone . . . was planned with insistence upon completeness in the light of modern demands on the teacher’s professional school, and is adequate to all present needs.”

Indeed it was. In addition to a proliferation of coat hooks and umbrella lockers, the new building featured nine classrooms and six seminar rooms, seating 850 and 132 students, respectively. Offices for the appointment secretary of the School of Education occupied the first floor, as well as a group of offices for the instruction of secondary education and an associated seminar room, the largest such room in the building, able to hold 170. Seminar rooms were provided for vocational education and agricultural education. The second floor held the library and administrative offices for the school, as well as the faculty room. There was also a seminar room and a laboratory for educational statistics.

One hundred years on, the building is largely intact, but a 2004 analysis revealed that chemical reaction between the concrete and underlying steel reinforcing bars was causing the steel to corrode. This, in turn, made the steel expand, cracking and spalling the ornamental reliefs on the exterior. Chunks began to fall, imperiling passersby below and leading to the installation of netting pending repair. Restoration will require new molds and castings of the ornaments.

Haviland Hall was designated a City of Berkeley Landmark in 1981 and in 1982 was added to the National Register of Historic Places (entry #8200).

Written by Craig Alderson