“Like Café-au-lait”

Haviland Hall boasts a remarkable sub-basement, hailed as the longest of its kind in the world, more than double its nearest counterpart in Germany and the only one in the United States. Yet for most of the past century, the sub-basement has been hidden from the building’s occupants.

Buried beneath the ground floor—“blasted out of solid rock,” as the Daily Californian reminded its readers—was a sub-basement stretching 135 feet under the building and measuring anywhere from 10 to 15 feet wide. With concrete walls nine inches thick, and “pillars projecting from the walls every eight feet to minimize echoes”, this subterranean tunnel was designed to be absolutely light and sound proof. It also featured a photographic dark room and a ventilation system that provided “washed” air through three underground openings.

The sub-basement was intended to test children’s eyesight and hearing. The standard visual and auditory tests administered at school sites were “extremely inaccurate, particularly the tests of hearing, due to the impossibility of finding in a school building light-proof and sound-proof conditions.”

Haviland’s tunnel was to remedy such testing deficiencies, and its primary instrument was the “acoumeter.” The acoumeter dropped a series of balls; “by measuring the distance at which a person ceases to hear [the sound], his auditory power can be computed.” The floor was marked off in feet to show the exact distance of the test subject from the acoumeter. The lab also had a tone variator, a mechanical device that generated tones of varying pitch by directing air over a resonator—similar to blowing over the top of a soda bottle. Inside the resonator was a piston which, when raised or lowered, would change the volume of the resonator and thus the pitch of the tone it generated.

The tunnel also tested children’s vision through visual acuity and color charts illuminated with standardized light. Daylight lacked constant illumination, resulting in inaccurate visual acuity tests. Accordingly, the new tunnel would be illuminated by huge daylight lamps, which threw reflected white light onto reading charts. It was also equipped with ordinary electric lights to demonstrate the contrast between the two. “This new laboratory will have the light thrown from above,” the newspaper reported, “the current of which will be kept at the same voltage and degree of brightness for every experiment. In this way every child will receive the tests under identical conditions.” As a dark room, the lab was also intended for research into space perception and stereoscopic vision—“important in such subjects as solid geometry and the plastic arts”—which would be conducted by projecting an ordinary photograph through a special lens apparatus to show the object both in its original and its three-dimensional form.

In addition to acuity testing, plans for the laboratory included research into the carrying power of the human voice. According to Joseph V. Breitweiser, the supervising professor, “Students of public speaking classes wishing to study acoustics, find the points of echo in the tunnel. By hanging cheesecloth drapes at these places, the echo could be eliminated, and a word spoken would carry clearly, instead of tumbling from one end of the hall to the other, as it does now” (Daily Californian, Dec. 3, 1924, p. 4).

“Because of the absence of distractions,” Professor Breitweiser predicted, “tests there will probably be extremely successful.”

The lab and its equipment were designated for use by any school within the state, and it was planned to bring in school children regularly for testing. With the state-of-the-art testing the new facility enabled, it would be possible to bring up to sixty children into the lab at a time “and within an hour and a half or two hours indisputably accurate tests of hearing and vision may be made.”

“This laboratory will undoubtedly be the means of remedying the present health conditions in the public schools,” Professor Breiwieser confidently concluded.

“The minute a child develops symptoms of eye or ear trouble of the sort which may be cured by means of our experiments, he will be brought by a nurse to our laboratory where he will be given all the specific tests applying in his case.”

The School of Education also made the tunnel available to other departments as well. The physics department, it was thought, would be particularly eager to take advantage of the light- and sound-proof environment to conduct its own experiments. There were also plans to increase the range of equipment in the lab to accommodate other fields of research. The General Electric Company’s research department provided equipment for the lab and was interested in the research results it produced.

How effective was the tunnel? In early December 1924 one intrepid Daily Cal reporter descended into the vault to find out. The experience the reporter recounted, of being swallowed by the silence and utter darkness of the subterranean chamber, is almost palpable.

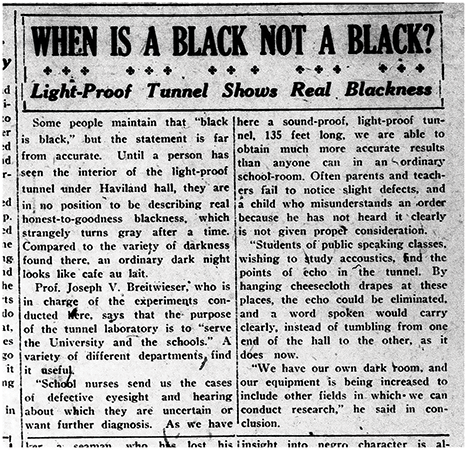

“When is a black not a black? Light-proof tunnel shows real blackness,” posed the headline. “Some people maintain that ‘black is black,’ but the statement is far from accurate,” the reporter wrote. “Until a person has seen the interior of the light-proof tunnel under Haviland hall, they are in no position to be describing real honest-to-goodness blackness, which strangely turns gray after a time. Compared to the variety of darkness found there, an ordinary dark night looks like café au lait.”